Five ships riding in the Downs in late December 1661 carried two English Regiments of New Model Army men.

One of these regiments comprised battle-hardened soldiers - dedicated Protestants and avid parliamentarians who had fought for France when Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell had agreed to send 6,000 men to help Louis XIV in his efforts to force the Spanish out of Flanders. Once they had captured Dunkirk, England would be granted sovereignty over the town, and could expel the Spanish privateers who had wreaked havoc on English merchant shipping in the Channel. All this had duly taken place, and the piratical Spanish had been cleared from the port, but Dunkirk was proving an expensive place to maintain, and it was rumoured many in the Restoration government of Charles II were questioning its value.

The annual allowance granted to Charles by Parliament was proving insufficient to maintain his indulgences toward his mistresses and the expenses of government. Sending a large part of the Dunkirk garrison to Tangier would at least limit the additional cost of maintain the newly acquired territory.

Many of those men were experienced veterans recruited in 1657 and formed into Lillingston's Regiment, one of the six regiments along with those of Morgan, Lockhart, Alsop, Cochrane and Clark. They had shipped to Flanders in 1657. In spite of their lack of experience in the protracted sieges that typified continental warfare Cromwell's redcoats soon gained a reputation for forthright actions and fierce fighting.

In late August the French planned to besiege St Venant and assigned Morgan's regiment to dig trenches. When Colonel Morgan ordered his men forward to the appropriate point they refused to stop there, and pressed their attack so hard they took three bastions, and the following day the defenders surrendered. The heavily fortified town had been taken in one day for the loss of ten English dead and less than twenty wounded.

The Protestant Regiments continued to enhance their reputation until the following year at the Battle of the Dunes they came up against the main Spanish Army of Flanders, which included 2,000 English Royalists.

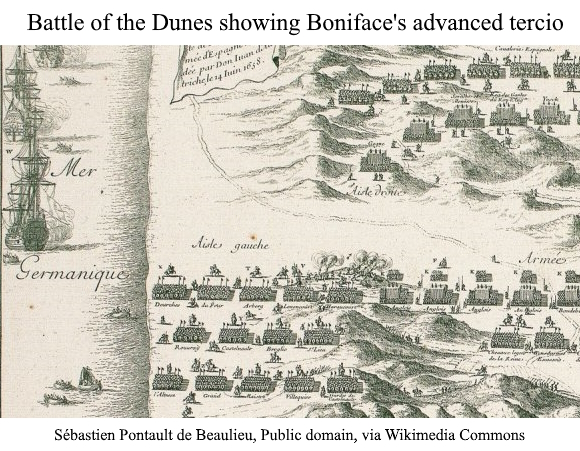

Battle of the Dunes

When the Parliamentarian Regiments approached the Spanish defensive lines they found themselves opposite Boniface's elite tercio square of pikes and muskets ensconced on the top of a steep sand-dune, some 45 metres high, in advance of the main Spanish line. The Spanish formation was reinforced with a detachment of Royalist English from the King's Own behind whom the Duke of York was positioned with his cavalry.

As Lockhart's ‘White' Regiment were drawn up in front of Don Gaspar Boniface's sand-hill they came under fire, and, not prepared to stand and take hits, they advanced, apparently not waiting for orders, scrambling up the steep face of the dune. Morgan ordered 400 firelock musketmen to flank the attack and sent Lillingston's ‘Blue' Regiment up the hill as well.

The volleys from the firelocks and the push of pike together managed to break the tercio. The Duke of York, fighting for the Spanish, led his cavalry in a charge against the flank of Lillingston's Regiment and was making some gains, but Morgan sent the other Parliamentarian Regiments forward and despite the valiant attempts of Boniface's men and the King's Own to rally and hold their ground, the Parliamentarians swept the field.

The victory had cost Lockhart's Regiment some 3 officers and 50 men dead and Lillingston's 1 officer and thirty or forty men, and the French lost a similar number overall.

With the Spanish losing the majority of their Flanders Army, reduced by about 5,000 killed, wounded or captured, they were unable to prevent the fall of Dunkirk, which was immediately handed over to the English, as agreed. Lockhart and Alsop's regiments were given garrison duties in Dunkirk and before long more than half of the English Parliamentarian troops were on garrison duty in and around Dunkirk and Mardyck. By September 2,000 English under Morgan were serving in Turenne's French Field Army, and in the remaining month of action the English took Ypres in a daring assault planned and led by Morgan and Commine was captured by the Scottish Guard under Colonel Andrew Rutherford.

In May 1659 when Lockhart became governor of Dunkirk he withdrew all the remaining men from the French army to strengthen the garrison which had been weakened by various losses. A few months later the regiments of Morgan, Cochrane and Clark were taken to England to help deal with the Royalist uprisings in August, leaving a total of 2,500 men.

When Charles Stuart was restored Charles II in May 1660, the whole army in England had been disbanded and thousands of soldiers made redundant. Only Moncke's Regiment - which had marched down from Coldstream on the Scottish Border to restore order when Richard Cromwell had resigned as Protector - had been reinstated as an active regiment. The army in Flanders had avoided that fate, but Lockhart was replaced by Sir Edward Harley, who took over Lockhart's Regiment, and before early in 1661 Robert Harley took command of Lillingston's Regiment.

Now, in November, Harley's Regiment of more than 900 men had been put aboard ship, destined for Tangier. The last three years had been tedious garrison duty, higher ranking officers had changed with the political climate in England, and many in the Regiment would be glad to be far away from Restoration England fighting against Moorish Muslims or resuming their war on Spanish Catholics. The pay on offer promised a good living, the climate in Tangier was said to be equitable and there should be opportunities for bettering one-self as the colony was enlarged and civilised. They knew other ships carried like-minded men.

The other regiment were recent volunteers. Although soldiers of the disbanded army had received their back-pay, as promised under the Declaration of Breda, and many had settled into civilian life peacefully and successfully taken up peacetime occupations, there were plenty of veterans of Cromwell's wars who were quick to return to the flag and sign up for this new venture in Tangier.

To the recruitment officers on Putney Heath on 14th October 1661, it made no difference whether the volunteer were Parliamentarian or Royalist, Catholic or Protestant; for many this was a chance to make a new start. Once they reached the Promised Land of Tangier, the Parliamentarians of Harley's regiment would, no doubt, find many old comrades amongst Peterborough's Regiment.

Fact Check

Main Source:

Riley, J., The Colonial Ironsides (Helion & Company, 2022)