The much feared Tercios formations of early 17th Century Flanders had evolved from experience gained in the Italian Wars of 1494–1559.

The use of large concentrations of archers and stands of pikemen reduced the effectiveness of heavy cavalry, which were anyway necessarily limited in numbers because of the high cost equipping, training and maintaining them, especially in contrast with the cheap weapons of pikemen. As a result the Spanish learnt from the Turks and replaced many of their heavy knights with light cavalry – jinettes - with little or no armour, employing lances and firearms.

Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba had been instrumental in reorganising the Spanish Army. In 1503 at the Battle of Ceringola he introduced the coronelia formation for infantrymen - where tightly grouped pikemen were flanked by swordsmen with bucklers and men with firearms – to resist French attacks and then go on the offensive. This seems to be the first battle won by the use of small arms, leading to the evolution of companies of 120 or 150 highly trained infantry or cavalry that could be combined in particular ways, according to need, into columns or colunellas, under colonels, of perhaps 400 men, and again into regiments of ‘tercios' of 1200 or 1500, generally including at least two companies of musketmen.

Alternatively companies could be combined in different formations of escuadrons of anywhere from 600 to 3000. Cordoba went on to develop the tactic of combining infantry, cavalry and artillery in battle. These formations were deployed successfully in ejecting the French from Italy.

Financed by resources from their widespread empire, the Spanish went on to wage almost continuous war on several fronts; their standing army growing from 20,000 in the 1470s to 200,000 in the 1590s. Training was the envy of other nations with new recruits being trained on duty in foreign garrisons before being sent to the front. Supply routes were established and maintained, and military organisation developed and adapted to suit prevailing conditions.

King Gustavas Adolphus and Elector Johann George as 'saviours' from the war - with cannons, rifles and bullets as medicines

Lightweight bronze cannon were mounted on wheeled carriages drawn by horses rather than oxen. These manoeuvrable guns could be deployed quickly and when used in significant numbers, firing iron cannonballs, they could destroy traditional defensive walls in a few days.

In response to artillery bombardment strategic towns were surrounded with a polygonal plan of low sloping walls to deflect cannonballs, with bastions from which defenders could enfilade anyone assaulting the defences. Attackers, unable to batter the walls had to fall back on the age old tactics of siege warfare, which demanded large armies that could be maintained for long periods and withstand attacks from relieving forces.

Where towns lacked such defences armies were still met in the field and battles took place, though these were rarely decisive in terms of ending a war.

In places, such as South America or the Philippines, where opponents knew they could not afford to fight a battle or defend a town they would resort to guerrilla warfare.

The Spanish Army developed the ability to succeed in all these environments, gaining a fearsome reputation throughout the world.

But even the seemingly infinite resources of their empire could not continue war on so many fronts – against the Dutch, the English, the French, the Portuguese and the Ottomans - and keep the indigenous citizens of their overseas colonies under control, indefinitely. Other countries increased their own overseas trade and improved their war machines.

Maurice of Nassau upgraded his country's army by standardising equipment and publishing training manuals to ensure uniformity of understanding on the battlefield. Gustavas Adolphus of Sweden devised ways of keeping several armies in action simultaneously.

But field battles rarely proved decisive - taking and holding strategic towns was much more significant.

For the Spanish, home-supplied resources of war materials and fighting men dwindled, the huge influx of gold and silver from the Americas fuelled rampant inflation and on occasion supplies failed, wages went unpaid and armies mutinied. As a result Spain had to conclude various treaties and agreements which reduced their influence and control.

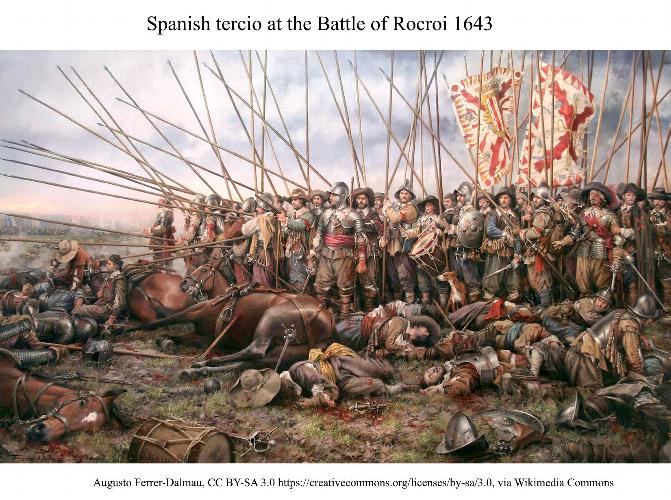

The Battle of Rocroi where the French defeated the Spanish Army of Flanders is often seen as the beginning of the decline of the Spanish Tercios. In truth it was but one victory, and the French were not strong enough to follow it up. But Spanish power was beginning to wane, as shown by its recognition of the Dutch Republic in 1648 and the ending of the Thirty Years' War with the Treaties of Westphalia in the same year.

Spain remained at war with France, and faced the Portuguese in their War of Independence initiated in 1640 under John IV of Braganza. In addition, in December 1654 Cromwell sent an English army to attack Spanish Hispaniola effectively starting the Anglo-Spanish War which resulted in 3,000 English Infantrymen being sent to aid France in its war against Spain in Flanders and the English navy blockading Dunkirk.

The Anglo-French forces won several battles against the Spanish, most notably the Battle of the Dunes where New Model Army Regiments attacked a Tercio ensconced on a high sand dune and forced its retreat, leading to the routing of the Spanish army. This defeat severely dented the reputation of the Spanish Tercios and resulted in the English occupation of Dunkirk.

1659 saw Spain and France declare a draw with the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees with territorial concessions on both sides, but the French Army had established some degree of parity with the Spanish.

By 1660 Spain, even after several defeats in Flanders, was still a mighty power with a large empire. Her army, by now reduced to perhaps 100,000, was matched by France and by the Dutch Republic, and even insular England, as a result of Civil War had an army of perhaps 70,000. Wars with England and Portugal continued to drain resources, but that did not prevent Many Spanish nobles casting jealous eyes in the direction of Tangier.

Fact Check

Most of the content of this article is derived from:

Parker, Geoffrey, The Military Revolution 1560-1660 A Myth? The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 48, No. 2 (Jun., 1976), pp. 195-214

King Gustavas Adolphus and Elector Johann George as 'saviours' from the war - with cannons, rifles and bullets as medicines

Lightweight bronze cannon were mounted on wheeled carriages drawn by horses rather than oxen. These manoeuvrable guns could be deployed quickly and when used in significant numbers, firing iron cannonballs, they could destroy traditional defensive walls in a few days.