The Dutch Navy

Sea Beggars

The origin of the Dutch navy can, perhaps, be traced to the 25 ships of the 'Sea Beggars' who captured the small port of Brielle in 1572 (1st April) and declared for William the Silent, giving the Dutch revolt a shot in the arm which resulted the whole of the provinces of Holland and Zealand rising against their overlord, Philip II of Spain.

War of Independence

The revolt developed into an independence movement and a government was formed. The newly established Dutch Republic created the five regional admiralties, three in Holland (Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Nooderkwartier) and one each for Zeeland and Friesland, funded by local taxes each responsible for building and manning its own ships.

The ports and shipyards of the maritime provinces of Holland Zeeland and Friesland nurtured a large seafaring population with nautical skills and easy access to the Baltic trade in supplies of wood, tar and other ship-building necessities.

The growth of the herring fleet and the complementary trade in grain with the Baltic States developed a lucrative entrepot business and created a huge maritime market. Individual cities were responsible for providing ships, known as director's ships, to protect the herring fleet and to escort the convoys of merchantmen from the predations of privateers especially those of Spanish Dunkirk.

The war of independence against Spain (now known as the eighty years war) continued. The Dutch fleet controlled the North Sea and broke all attempts to defeat them by blockading their ports and as early as 1585 imposed its own blockade on Antwerp and the Flemish Coast to prevent the Spanish supplying their troops.

The combination of cheap provisions, entrepreneurial skills and windmill powered wood-saws led to a rapid development of shipping technology that allowed shipping of Dutch Republic to more than hold its own against larger and more populous competitor countries.

Beyond the North Sea

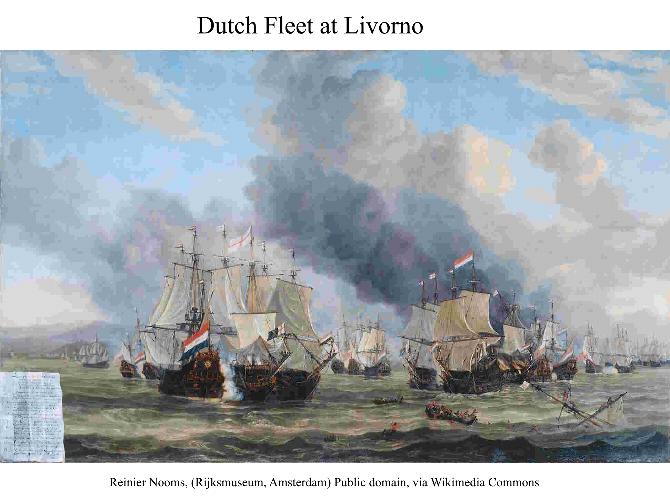

Development of a system of shared risk through an early stock-market mechanism and modern banking encouraged investment in trade and led to expansion of its operations beyond its home waters. By escorting convoys of their own merchant ships through the Channel and into the Mediterranean the Dutch fleet enabled the Republic to expand its operations massively, pushing Portuguese and Spanish trade into decline and, with the rise of the East India Company, taking over trade routes from all other nations worldwide.

In 1607 the Dutch had the temerity to attack the Spanish in their home port of Gibraltar fleet and destroyed the main force of a large Spanish fleet under construction there.

The huge Dutch merchant navy, outnumbering the total of all rival nations combined was an almost instant source of extra ships that the admiralties could call on to supplement their own standing fleet, although these ships would generally be armed with fewer cannon.

In 1639 the Dutch Fleet numbering about thirty ships under Maarten Tromp and was capable of engaging a large combined Spanish and Portuguese fleet of about sixty ships sent to reinforce and resupply Spanish Army of Flanders and delaying it long enough for the five admiralties to hire and arm an extra sixty-five merchantmen, giving a combined fleet of nearly a hundred ships assembled within a few weeks.

Dutch tactics were generally to send in fire-ships or to grapple and board the enemy ships. A month after they first challenged the Spanish fleet, the Dutch won a decisive victory destroying a reported 35 ships for the loss of perhaps less than 10 if their own.

Decline of the Dutch Navy

In the Treaty of Munster, 1648, Spain recognised the independence of the Dutch Republic and the need for a strong navy to blockade Flanders was removed and it seems this led to some neglect of the Dutch Fleet.

Rise of the English

The English Commonwealth built a strong navy during the war of three kingdoms to challenge the Royalist Squadron and safeguard Cromwell's supply lines to Scotland and Ireland. With the imposition of a 15% tax on merchant shipping on 10th November 1650 the Rump Parliament continued its rapid expansion of the navy to protect its shores against a perceived threat from its Catholic neighbours in Europe, and to counter privateers, especially those of Spanish Dunkirk.

This large navy was expensive to maintain and the English Parliament eyed the Dutch domination of maritime trade with envy and in order to protect trade with its American colonies and increase its revenues it passed the Navigation Ordinance of 1651 forbidding foreign ships from bringing goods to England.

The English Commonwealth threat to use its strong modern navy to enforce this Ordinance led to the First Anglo-Dutch War in 1652.

War with the English

English ships were larger and carried heavier guns with greater range than the Dutch, and relied on standing off and battering the enemy ships with cannon-fire from a distance. When the Dutch ordered Tromp to sail against the English he complained that the English fleet had twenty ships more powerful than even his flagship Brederode.

The Dutch could again call on their merchant fleet and quickly mustered a hundred ships. Their ships were more agile, but when the English refused to be brought to close combat the Dutch suffered against the concerted English attacks.

The New Navy

The Dutch recognised the need to modernise their fleet with heavier ships to compete with the English and in 1653 they placed orders for 60 ships and began building what is now known as their 'New Navy'.

By July 1661 when the Earl of Sandwich was sailing with seventeen ships with a total of 668 guns, to secure Tangier against expected challenges from the Dutch and Spanish ready for Peterborough's occupation force, Ruyter was sailing with seventeen ships totalling 700 guns nominally to help the Spanish guard their treasure fleet.

Thurloe's State Papers put the Spanish allies of the Dutch with twenty ships of 30 plus guns, the same number as Portugal, the English allies.

Fact Check

Main Source:

Bruijn, J. R., The Dutch Navy of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Liverpool: Liverpool Univ Press, 1993)