The Knights of Malta

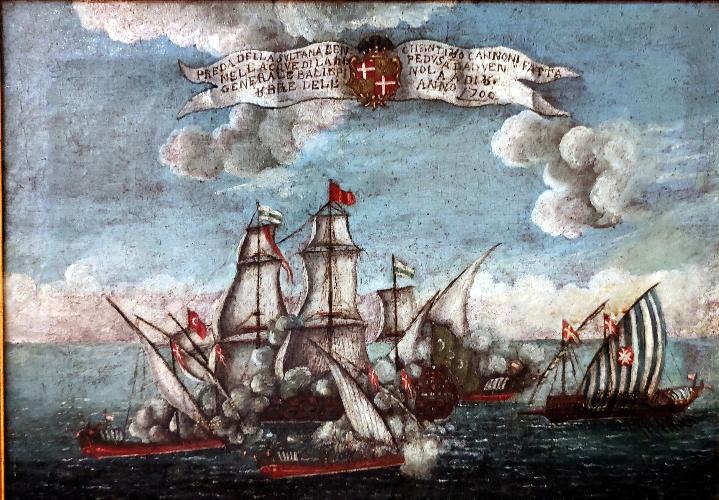

Naval scene with arms of Grand Master Perellos

Painting by Kind permission of Palazzo Falson, Mdina, Malta

Who were the Knights of Malta

Following the capture of Jerusalem in 1099 a group of crusaders formed a religious order to support the city hospital dedicated to St John the Baptist – originally established as a hospice by Benedictine monks to care for pilgrims of any religion.

Defenders of Christianity

In 1113 a Papal Bull issued by Paschal II recognised the Knights of the Order of St John, known as the Hospitallers. From about this time the Hospitallers duties included defending Christians against Muslims.

Christians v Christians

When Jerusalem was recaptured by Muslim forces in 1291 the Hospitallers moved to Cyprus. Due to difficult relationships between the Order and Henry II of Cyprus, the Grand Master Fouques de Villaret decided to resettle the Hospitallers on the Byzantine held island of Rhodes.

The Byzantine Emperor refused the suggestion and it took Villaret several years to complete the conquest of the island. Once securely based in Rhodes, the Hospitallers waged unceasing war against Muslim ships whilst defending the island from all-comers - Christian and Muslim alike.

In 1522 after a 6 months siege by more than 100,000 troops, the Turkish Sultan 'Suleiman the Magnificent' forced the Knights to surrender, allowing the survivors to leave under condition they swore an oath to no longer fight against Muslims.

Malta

Once resettled on Malta the Order broke its oath and resumed its war against Muslim shipping. Suleiman sent an army of 40,000 against the Hospitallers, who held out for 6 months, inflicting heavy losses on the invaders and forcing the Muslims to withdraw. The Knights refortified the island and resumed their ‘Corso'. For the next 150 years they attacked Muslim shipping and anyone suspected of transporting Muslims or their goods. They released many Christian slaves and captured Muslims to ransom, sell in the lucrative slave markets or condemn to row their fleet of eight galleys.

The Fleet of the Knights of Malta

The lateen rigged galleys were highly manoeuvrable, being able to set the sails to take advantage of any wind direction, and sail much closer to the wind than most other ships. The sleek hull and twenty or more benches with 6 men rowing on each side, ensured the ability to attack at speed. The galley would fire its forward facing cannon and ram an enemy ship so that a boarding party could leap onto the deck of their quarry and engage in hand-to-hand combat. The hulls of the Knights of Malta galleys were traditionally painted red above the waterline and white below; from 1625 the flagship of the flotilla had a black hull.

Knights of Malta - Actions

The fearsome Knights were sworn to attack Muslims even if outnumbered 3 to 1, and often suffered considerable casualties in securing victory.

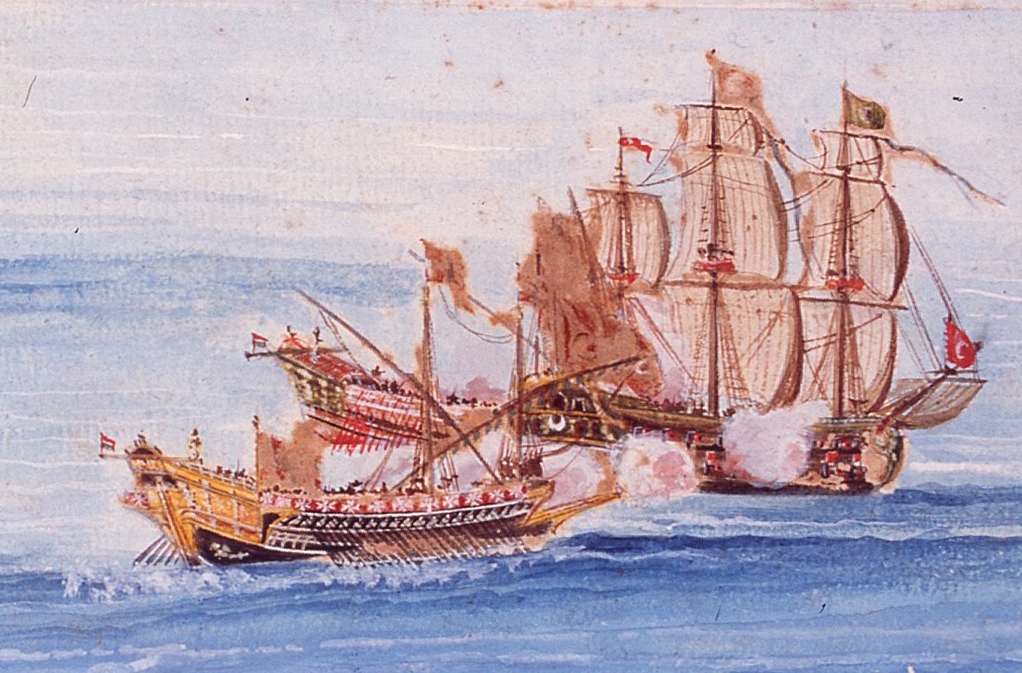

Painting by Kind permission of Palazzo Falson, Mdina, Malta

This detail from a watercolour in Museum Palazzo Falson, Mdina, Malta, shows the Knights of Malta flagship, recognisable by its black hull, with sails furled for action, rowing at full speed into the attack with cannon firing. The boarding party of Knights and men-at-arms stand on the foredeck ready to leap onto the Muslim vessel, with back-up lining the gangway all down the galley. A second galley, with the usual red hull, is shown attacking the far side of the Corsair.

Painting by Kind permission of Palazzo Falson, Mdina, Malta

The painting, here shown in full, depicts the defeat of the infamous renegado, Beccassa de Tripoli who, having fought alongside the Knights in their Corso changed sides to lead a group of Muslim Corsairs. In 1638 the General Balj Carajut caught up with the ‘Ammiraglio di Barbaria' off Calabria and despite the renegade's 3 ships, 45 cannon and 500 men defeated him, taking more than 200 Christian slaves and all the Corsairs' plunder along with the 3 ships.

Another confrontation in 1668, described by Bartolomeo dal Pozzo in his Historia della Sacra Religione saw 4 galleys of the order ram the Algerian Corsair Sultana Benghen to release 40 Christians, including the Gentildonna Palmeritana, capture 152 Muslims and take 4,000 Reals. In this action two Knights and 6 men-at-arms were killed and 25 of their men wounded.

Maltese Fleet as an example to English Tangier

Upon acquiring Tangier in 1662 English merchants and many of Charles II's advisers were keen to expand the lucrative trade with the Lavant and Africa. Tangier would provide a base for a Mediterranean fleet which would force the Muslim Corsair states to refrain from attacking English ships. After several years of mixed results it was decided that the success of the galleys of the Maltese Knights of St John and the Tuscan Knights of St Stephen, based in Livorno, set examples the English should follow. Charles II's brother, James Duke of York, was impressed by the historic chivalric code of the Knights and persuaded Charles to purchase two galleys.

In 1669 the galleys were ordered, one from Livorno and another from Genoa at a total cost of more than £23,000. Pepys foresaw operating a galley alongside two frigates could provide a constraint on the Algerian corsairs which would be ‘as to have a(n English) fleet lie before their port'.

This typically impetuous decision by the Stuart King and his officials lacked the planning needed for success. Whereas the Knights' well established predations on Muslim shipping supplied a constant source of slaves to operate their galleys, and the French, whom Charles loved to mimic, sent criminals to the galleys, England had no such traditions. They would have to persuade other navies to sell them slaves, or buy them in the open slave markets. But slaves were in short supply, England was not even a catholic country, and no-one, even the Knights of Malta was prepared to cooperate. Jean Baptisite Duteil, a French relative of a Knight of Malta, was put in charge of the English galley project, and, in due course managed to buy 51 slaves in the Maltese slave-market for £6,000, including the usual taxes paid to the Knights of Malta.

The Livorno galley, named Margaret, began sea trials in 1672, and was in operation by 1674 with a crew of English seamen and fifty soldiers from the Tangier garrison. A new source of slaves was found in American Indians deported from the New World for their part in activities against the English Colonies, but these were few and by no means a regular supply. Further these men had been converted to Christianity and it did not meet with universal approval to chain Christian men to the galley oars. A year later command of the Margaret passed to Captain Hamilton of the English Navy.

Meanwhile Admiral Sir John Narborough's fleet was sent to demand the Corsair States sign treaties protecting English merchant vessels from their attacks. Based in Malta, his raid on Tripoli in particular pleased the Knights of Malta by releasing more than 70 Maltese citizens from slavery. Narborough's continued campaign over the next few years forced Tripoli, Tunisia and Algeria to respect English shipping. This temporarily reduced the need for policing against corsairs and consequently reduced the opportunities for capturing slaves.

The English galley venture was, therefore, a limited success, initially because the English lacked experience in operating galleys and later because of the changed circumstances. At the end of the second year, 1676, the venture was discontinued. The second galley did not materialise and the Margaret was left to rot at its purpose built galley dock; the slaves, still housed in their Tangier bagnio were transferred to work on the ambitious mole-building project.

Tangier's co-operation with the Knights of Malta was born of temporary necessity and was short-lived:

The English and the Hospitallers fought a common enemy in that they both attempted to curtail the operations of Muslim Corsairs, but whereas the English tried to treat with the sponsoring countries to leave their own merchants free from molestation in a mutual non-aggression pact, the Knights attacked any Corsair and considered every Muslim trading vessel a fair target.

Main sources:

The Warships of the Order of St John 1530-1798 by Joseph Muscat

Charles II, Louis XIV and the Order of Malta, Allen, D.F., European History Quarterly Vol 20 1990 pp323-340